By Rona Kobell

Small fish such as herring, menhaden and anchovies are twice as valuable when left in the ocean as when caught in commercial fisheries, according to a new report which calls for management agencies to re-examine how they set their forage fish harvest limits.

The team of scientists from around the country also recommended that catches for most forage fish species should be cut in half to protect both their stocks and the huge array of species that eat them.

“The demand and price for these fish has been increasing, while their crucial ecological role has largely been ignored,” said Ellen Pikitch, executive director of the Institute for Ocean Conservation Science at Stony Brook University in New York, who chaired the task force. “If these trends continue, the catch being massive and demand increasing, then we may see catastrophic losses of ocean life.”

The report from the Lenfest Forage Task Force report, “Little Fish, Big Impact: Managing a crucial link in ocean food webs,” is the most comprehensive global look at forage fish science and management to date. It analyzed available information about forage fish from around the world – including the Chesapeake Bay – and used sophisticated computer modeling to better understand the role of such fish as capelin and sardines in marine ecosystems.

“There was an extensive amount of original analyses and modeling that went into this,” said Ed Houde, a professor of fisheries science at the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science and a member of the task force. “We didn’t just pull these recommendations out of a hat.”

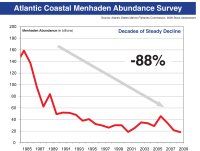

The role of forage fish, particularly menhaden, has fueled growing controversy in the Chesapeake. Many recreational anglers contend that commercial fishermen harvest too many of the small fish, depriving predators such as striped bass and weakfish of adequate food. Although the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission, which manages migratory fish along the East Coast, took action last fall to cut menhaden harvests, the report implies it did not go far enough.

The Bay has already suffered sharp declines of other forage fish in addition to menhaden: Shad and river herring are at record lows in the Chesapeake. River herring – alewife and blueback herring – were claimed to number

3 billion in the Potomac River during spring spawning runs in the late 1800s, but are now at record lows all along the East Coast and are under review for possible protection under the Endangered Species Act.

Concern about forage fish is global. They are small species which often form large schools and provide a critical link in the aquatic food chain by converting plankton into food for predator fish, birds and mammals.

The huge abundance of forage fish inspired the belief that the oceans could not be overfished. But today, many species of forage fish are themselves substantially depleted because of fishing pressure. About 31.5 million metric tons are caught globally each year, making up about 37 percent of the entire wild marine fish harvest.

Most are not consumed by people; 90 percent are processed or “reduced” into fish meal and fish oil, which are used to feed livestock, for aquaculture and other purposes. In recent years, the majority of the forage fish harvest ends up being processed into food for aquaculture, rather than feeding wild fish in the sea, the task force found.

Globally, the catch of forage fish is worth about $5.6 billion, the report said. But it added that forage fish were worth twice as much – $11.3 billion – when left in the water where they serve as food that supports the production of commercially important species such as salmon, tuna, striped bass and cod.

“This analysis understates the full economic value of forage fish, because we have only looked at the value to commercial fisheries production,” Pikitch added. “There is also a very important recreational fishery, and many of these are dependent on the forage fish that feed those important recreational fish.”

The report found that 75 percent of the ecosystems examined around the world contained one or more predatory fish that depend on forage fish for at least half of their diet. Many species, such as whales and seals, often rely heavily on forage fish, too. Sea birds were found to be particularly susceptible to forage fish declines.

The collapse of sardine populations off the California coast caused the diet of a seabird, the marbled murrelet, to shift to lower quality prey, which may have reduced reproduction which, in turn, contributed to its listing under the Endangered Species Act. Elsewhere, declines in species as varied as African penguins, Peruvian pelicans, several species of cormorants, the Peruvian booby and a number of other birds have been linked to declines in forage fish.

Even when forage fish are adequately protected to maintain their own populations, the report said that traditional fisheries management – which typically aims at maintaining the maximum sustainable yield for an individual species – does not ensure that enough are left to support fish, whales, seals, birds and other species that depend on them, a situation called “ecosystem overfishing.”

“With single species management you try to figure out what the best yield is that you can get from that species,” Houde said. “We don’t think enough about, or calculate, the demand by predator fish such as striped bass and bluefish, or tuna and salmon, for forage fish.”

The report said forage fish are as vulnerable to overharvesting and sudden collapses as other fish species. As a result, traditional management techniques may not protect their numbers. Many forage fish form schools, probably as a defense against predators. But the schools are easily targeted by modern fishing techniques that use spotter planes and sophisticated sonars to find fish and report their location to fishing boats. Such effective harvest methods can result in high catches even while stocks are in decline, which means reliance on catch data alone to determine stock health can mask the true state of the population, leading to a collapse, the report said. Also, because forage fish tend to be shorter-lived than larger predator species, their abundances may vary rapidly.

Even when overall stocks are healthy, the concentration of catches in a particular area can deprive local predators of an adequate food supply, something called localized depletion. Birds and marine mammals, in particular, have been shown to be vulnerable if too few fish are available during breeding seasons, the report said.

The panel concluded that to protect forage species and maintain healthy ecosystems, managers should try to leave twice as many forage fish in the water as needed to maintain the maximum sustainable yield under traditional management.

“We didn’t conclude that you shouldn’t fish for forage fish,” Houde said. But the task force recommended that the less information that is available about the population – and the less they know about predators that depend on it – the more cautious managers should be.

Conversely, in well-studied systems, where there is also good information about predator demand, “you might be able to fish harder and take more,” Houde said.

While the report examined the role of forage fish across the globe, it also included the Chesapeake among a number of case studies. Recent menhaden catches have left only about 9 percent of the spawning stock in the water, which the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission last fall concluded was too low after a recent stock assessment showed overfishing had occurred in 2008 and a number of previous years. The commission recently set its first coastwide harvest limits for menhaden. It called for leaving a minimum of 15 percent of the spawning stock in the water, with a goal of eventually protecting 30 percent.

But the task force report said menhaden warrant more precautionary management and suggested that further protections may be warranted, especially in the Chesapeake, where a disproportionate amount of the menhaden catch takes place.

Houde called the ASMFC action “a step in the right direction” but said that its new catch levels remain “on the risky side,” in part because they may not protect enough for species that depend on menhaden, from striped bass to birds.

“Fishing is not going to extirpate menhaden,” Houde said. “But if you are fishing at the traditional high rate, one would think that predators on menhaden must be suffering some kind of consequences, and people have recognized what the problem is: It is the localized depletion problem.”

The ASMFC has indicated that it plans to take additional management actions to better account for the ecosystem services of menhaden, such as ensuring adequate food for other fish. But scientists advising the commission have had difficulty determining what that population level should be.

Houde said the task force’s report could help provide direction. “Basically, this is guidance for setting limits on how much biomass you should conserve, and what fishing rates you should incorporate, based on what you know – not just about forage species, but how much you know about demand by predators in the ecosystem.”

The task force was convened by the Lenfest Ocean Program, which supports scientific research on management challenges facing the global marine environment. The program, established by the Lenfest Foundation in 2004, is managed by the Pew Environment Group.

The task force report is available at: www.oceanconservationscience.org/foragefish/

This article is from the Chesapeake Bay Journal